Satie, Ravel, Poulenc, Vol. 5

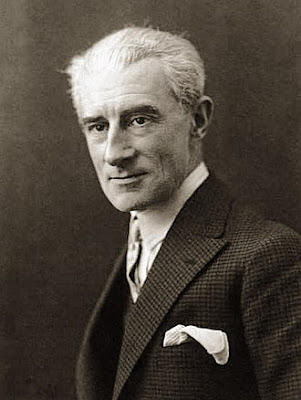

In this installment of Manuel Rosenthal's three-part musical memoir, he completes his recollections of Maurice Ravel in his final years. Previous entry here.

II. Ravel, con'td

I knew Ravel intimately during the last eleven years of his life. Because I was so much younger—almost forty years—I think he told me things he might not have told to friends nearer his age. Perhaps he felt as if he were talking to a child—he was seldom guarded. I remember once, walking on the boulevard, he kept silent for a very long time. I didn’t dare say a word; I was waiting for him to speak. When he spoke at last he just followed his thoughts—it had nothing to do with what we were saying. He said, “You know, I think it’s very difficult for an artist to marry, because you never know how much harm you do to your companion. Perhaps it’s too selfish to marry—you never know how wicked you will be, unwittingly.” I’m sure this was his way of explaining his solitary life.

One afternoon when Ravel was sick, in the last years of his life, he was in a very gloomy mood. All during lunch he had kept silent. It was silly on my part, but as a young man I was without tact, so I said, “If you were asked to choose the music for your funeral, what would you choose?” He smiled and said, “Oh, that’s easy.” I said, “What, you have something in mind?” He replied, “Yes, long ago I decided it would be L’Après-midi d’un faune, by Debussy.” I said, “Why that? You don’t need Chopin’s Funeral March, but The Afternoon of a Faun?” Ravel said, “In my opinion that’s the only perfect piece of music ever written, because it doesn’t appear to have been composed. It sounds as if Debussy were right in front of you, writing it down. It flows like an improvisation, and that’s the best compliment one can pay as a composer. That is real perfection.” With many wonderful composers, even better ones than Debussy—Mozart, Wagner—if you are a composer you know that there is a little trick that enabled him to do this or that, to bring it all together. Ravel said, “L’Après-midi d’un faune is seamless, without tricks.” The dream of all composers is the musical work that seems to have written itself. I dislike the word “improvisation,” but the music should sound unforced. Ravel always said, “If it looks like the work is well built, carefully constructed and thought out—that’s wrong! It always had to sound as if you are improvising in front of the public.”

Ravel asserted that every composer’s ambition was to write a nice waltz but that, in his opinion, only one succeeded: Johann Strauss. In spite of his humility, Ravel himself succeeded three times: in La Valse, in Valses nobles et sentimentales, and in the strange “Danse des Rainettes” from L’enfant.

Ravel sat next to his librettist Colette at the premiere of L’enfant. When it was over, his only remark was, “Isn’t it amusing?” That was a mask; Ravel was hiding. That was part of the French tradition to which Ravel was very proud to belong: restraint. He once said to me, “You know, in the time of Louis XIV, you never said you were ill. When someone asked how you were you always said, ‘just fine.’ You didn’t have the right to bother other people with your problems.” Ravel never complained, even though he was rarely in good health. Even when he wrote a letter (he had a telephone but he loved to write letters), he wrote in a traditional French way, very formal and elegant, and always ending, “je suis votre serviteur…”

Ravel loved young musicians, even those who were always attacking him. When I was young I went to one of a series of performances oganized by Count Etienne de Beaumont. That evening they were playing Salade by Darius Milhaud, a ballet with costumes and scenery by Andre Derain. By chance Ravel sat next to me; this was in 1924, and I hadn’t yet met him. He was with his close friend Cypa Godebski, half-brother of the famous Misia Sert. He was really Ravel’s closest friend, they saw each other almost every day. At the end of Salade Ravel applauded very loudly, shouting “Bravo, Bravo!” Godebski said, “But Maurice, you don’t know what this Milhaud says of your music—terrible things!” Ravel said, “Oh, that’s all right, that belongs to his age. He’s a wonderful composer, very gifted, I enjoyed his music. I don’t care if he insults me—that’s his generation.” It was only after L’enfant that some of the younger composers began to admire Ravel. After the premiere in Monte Carlo, Poulenc came up to him and apologized for having been “anti-Ravelean.” To Poulenc’s surprise Ravel thanked him, saying, “Never mind. There have been too many people writing bad Ravel anyway.”

Until shortly before his death in 1937, critical opinion was often unfavorable to Ravel. Few believed he was a serious composer! Even Georges Auric wrote a few years before Ravel died that Ravel was a “composer of the salon.” Arthur Honegger did not like him either. Ravel had long expected all that. He knew you could not be recognized easily if you were introducing something new to the world. Only once did I see him angered by his critics. We were in Montfort l’Amaury, and the postman brought the newspaper. Ravel said, “Ah, an article on me—‘Le Magicien de Daphnis.’” He exclaimed, “I am not a magician! I’m just a composer. Why can’t they say something serious about what I’m doing! I’m not a sorcerer, I’m just a musician!”

When Ravel’s health began to fail he remained very clear in mind, but his reflexes didn’t function. He couldn’t hold a pen, so I went with him every year to sign for his royalties. In that way I knew how much he was getting—it was very modest! Today his estate collections millions of francs! Well, that’s the way it is.

Next: The lively, liberal, tuneful Poulenc.

II. Ravel, con'td

I knew Ravel intimately during the last eleven years of his life. Because I was so much younger—almost forty years—I think he told me things he might not have told to friends nearer his age. Perhaps he felt as if he were talking to a child—he was seldom guarded. I remember once, walking on the boulevard, he kept silent for a very long time. I didn’t dare say a word; I was waiting for him to speak. When he spoke at last he just followed his thoughts—it had nothing to do with what we were saying. He said, “You know, I think it’s very difficult for an artist to marry, because you never know how much harm you do to your companion. Perhaps it’s too selfish to marry—you never know how wicked you will be, unwittingly.” I’m sure this was his way of explaining his solitary life.

One afternoon when Ravel was sick, in the last years of his life, he was in a very gloomy mood. All during lunch he had kept silent. It was silly on my part, but as a young man I was without tact, so I said, “If you were asked to choose the music for your funeral, what would you choose?” He smiled and said, “Oh, that’s easy.” I said, “What, you have something in mind?” He replied, “Yes, long ago I decided it would be L’Après-midi d’un faune, by Debussy.” I said, “Why that? You don’t need Chopin’s Funeral March, but The Afternoon of a Faun?” Ravel said, “In my opinion that’s the only perfect piece of music ever written, because it doesn’t appear to have been composed. It sounds as if Debussy were right in front of you, writing it down. It flows like an improvisation, and that’s the best compliment one can pay as a composer. That is real perfection.” With many wonderful composers, even better ones than Debussy—Mozart, Wagner—if you are a composer you know that there is a little trick that enabled him to do this or that, to bring it all together. Ravel said, “L’Après-midi d’un faune is seamless, without tricks.” The dream of all composers is the musical work that seems to have written itself. I dislike the word “improvisation,” but the music should sound unforced. Ravel always said, “If it looks like the work is well built, carefully constructed and thought out—that’s wrong! It always had to sound as if you are improvising in front of the public.”

Ravel asserted that every composer’s ambition was to write a nice waltz but that, in his opinion, only one succeeded: Johann Strauss. In spite of his humility, Ravel himself succeeded three times: in La Valse, in Valses nobles et sentimentales, and in the strange “Danse des Rainettes” from L’enfant.

Ravel sat next to his librettist Colette at the premiere of L’enfant. When it was over, his only remark was, “Isn’t it amusing?” That was a mask; Ravel was hiding. That was part of the French tradition to which Ravel was very proud to belong: restraint. He once said to me, “You know, in the time of Louis XIV, you never said you were ill. When someone asked how you were you always said, ‘just fine.’ You didn’t have the right to bother other people with your problems.” Ravel never complained, even though he was rarely in good health. Even when he wrote a letter (he had a telephone but he loved to write letters), he wrote in a traditional French way, very formal and elegant, and always ending, “je suis votre serviteur…”

Ravel loved young musicians, even those who were always attacking him. When I was young I went to one of a series of performances oganized by Count Etienne de Beaumont. That evening they were playing Salade by Darius Milhaud, a ballet with costumes and scenery by Andre Derain. By chance Ravel sat next to me; this was in 1924, and I hadn’t yet met him. He was with his close friend Cypa Godebski, half-brother of the famous Misia Sert. He was really Ravel’s closest friend, they saw each other almost every day. At the end of Salade Ravel applauded very loudly, shouting “Bravo, Bravo!” Godebski said, “But Maurice, you don’t know what this Milhaud says of your music—terrible things!” Ravel said, “Oh, that’s all right, that belongs to his age. He’s a wonderful composer, very gifted, I enjoyed his music. I don’t care if he insults me—that’s his generation.” It was only after L’enfant that some of the younger composers began to admire Ravel. After the premiere in Monte Carlo, Poulenc came up to him and apologized for having been “anti-Ravelean.” To Poulenc’s surprise Ravel thanked him, saying, “Never mind. There have been too many people writing bad Ravel anyway.”

Until shortly before his death in 1937, critical opinion was often unfavorable to Ravel. Few believed he was a serious composer! Even Georges Auric wrote a few years before Ravel died that Ravel was a “composer of the salon.” Arthur Honegger did not like him either. Ravel had long expected all that. He knew you could not be recognized easily if you were introducing something new to the world. Only once did I see him angered by his critics. We were in Montfort l’Amaury, and the postman brought the newspaper. Ravel said, “Ah, an article on me—‘Le Magicien de Daphnis.’” He exclaimed, “I am not a magician! I’m just a composer. Why can’t they say something serious about what I’m doing! I’m not a sorcerer, I’m just a musician!”

When Ravel’s health began to fail he remained very clear in mind, but his reflexes didn’t function. He couldn’t hold a pen, so I went with him every year to sign for his royalties. In that way I knew how much he was getting—it was very modest! Today his estate collections millions of francs! Well, that’s the way it is.

Next: The lively, liberal, tuneful Poulenc.

Comments

Post a Comment